This article is part of a series celebrating the 20 years of Blender as a free and open-source software, edited by Blender producer Fiona Cohen and first published alongside the Blender Foundation Annual Report 2022.

About the author

Jim Thacker edits the technology news website CG Channel. He was previously editor of 3D World magazine, has worked on books from Focal Press and Design Studio Press, and has been a technical writer for a lot of CG software developers, including, on occasion, the Blender Institute itself.

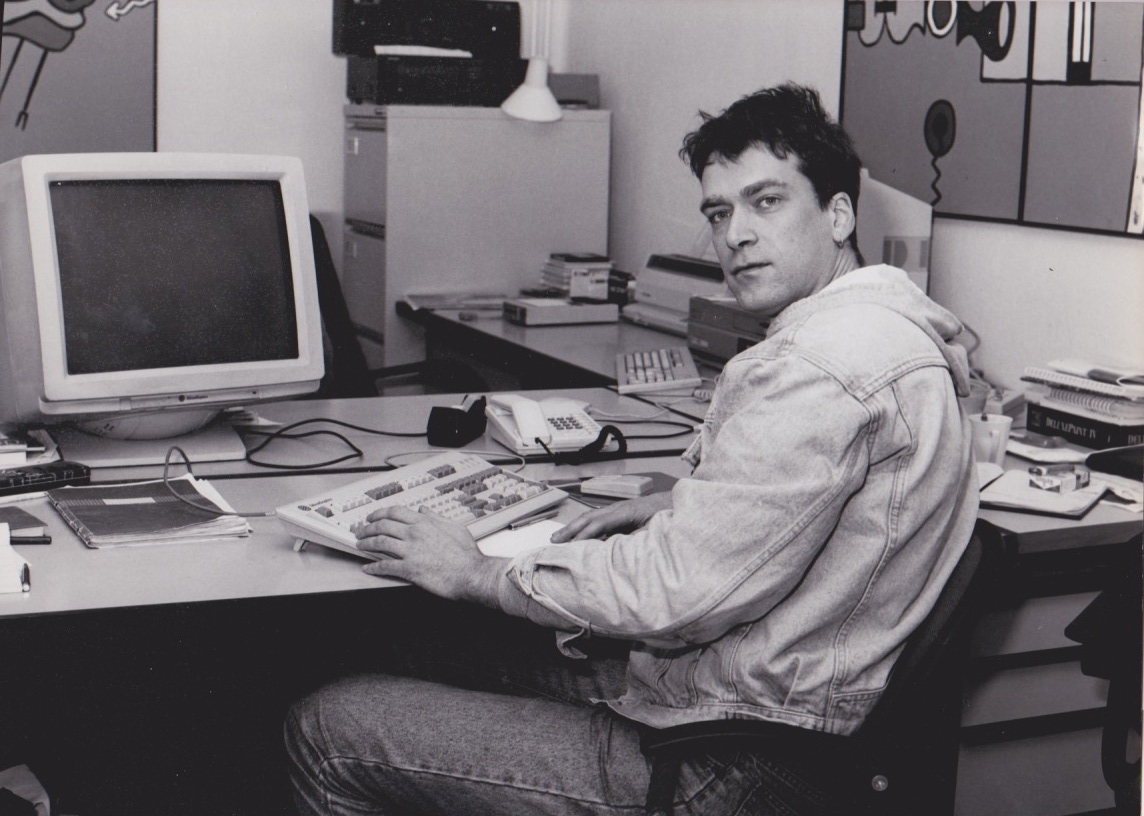

My career as a visual effects journalist coincides almost exactly with Blender’s existence as an open-source application. As the new editor of the newsstand magazine 3D World, one of the first stories I ever commissioned was on the original Free Blender crowdfunding campaign, followed a few years later by a series of production diaries from the set of the first Blender open movie.

Later, as the editor of the technology news website CG Channel, I covered subsequent, more ambitious attempts at open movie-making, the industry’s own shift towards open-source technology and, eventually, Blender’s use in the production of Oscar and Emmy Award-winning films.

The next paragraphs represent my pick of the milestones in Blender’s movie history: the key steps (and occasionally, missteps) along its path from initial release to industry staple. It isn’t a definitive history, but I hope that it gives an idea of how the software was seen by outsiders: not the diehard open-source advocates, but those engaged in the day-to-day business of making movies.

2002 – 2006: Free Blender

If anything, the need for open-source 3D software was even greater in 2002, when Blender was first released under the terms of the GNU General Public Licence, than it is today. This was a period when the main applications used in visual effects and feature animation cost thousands – in some cases, tens of thousands – of dollars, leading many students and freelance artists to resort to cracked software, while some studios were still using IRIX-based SGI Octane workstations in production. (As the decade wore on, most would be recommissioned as display cabinets or beer fridges, while their rendering duties were taken over by much less expensive Linux boxes.)

Yet the open-source apps bulking out the cover discs of contemporary computer graphics magazines were, by and large, an unprepossessing bunch: programmers’ pet projects, or hobbyist tools intended for teenagers looking to mod video games. Two things separated Blender from the pack.

Firstly, ambition: even before the first open-source release, Ton had established the non-profit Blender Foundation, meaning that right from the start, Blender was developed not by a loose-knit community of bedroom coders, but through an organization akin to a commercial software developer. And secondly, the size and dedication of its user base: long before Kickstarter, at a time when just buying things online was still a novelty, the Free Blender crowdfunding campaign was able to raise the €110,000 needed to buy the source code back from investors in Ton’s previous company, Not a Number. There was still a long road ahead of it, but Blender was on its way.

2006 – 2011: Developing by doing

Another thing that distinguished Blender from most other early open-source graphics tools was Ton’s insistence that it should be possible to use the software in production – or at least, under conditions similar to those of a commercial production. And so, in 2005, work began on Elephants Dream, the first Blender open movie.

‘Movie’ is an ambitious description for what is actually a nine-minute animated short, completed at a fraction of the cost of a typical Pixar production. But the €120,000 budget – raised through pre-orders of DVDs and a grant from the Netherlands Media Art Institute – meant that Elephants Dream had a price-per-frame in the same ballpark as indie animated features of the time.

More importantly, the new render pipeline created during its production became part of the public release of Blender: a pattern of developing by doing that became formalized in 2007 with the foundation of the Blender Institute to oversee the production of future open movies.

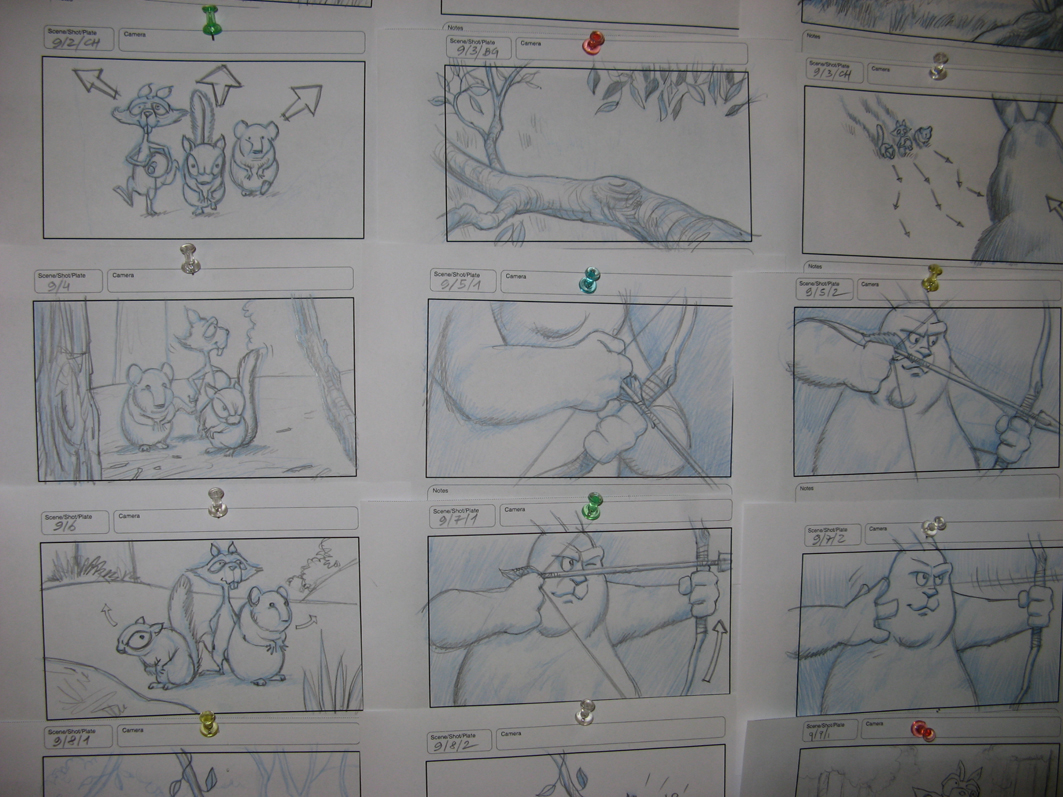

As a promotional tool, Elephants Dream was something of a mixed blessing: dark, semi-abstract, and adult in a way that most English-language animations of the time were not. But its successor, 2008’s Big Buck Bunny, was a viral hit, channeling an underlying streak of cartoon sadism into a more familiar Looney Tunes format.

Its cast of cute (ish) woodland critters – released, like all of the other assets from the short, under a Creative Commons licence – proved irresistible to marketers, with images from the movie popping up in everything from pamphlets for the Boy Scouts of America to ads for Google phones. Awareness of Blender began to spread outside the open-source community.

2011 – 2014: Conquering Hollywood by stealth

Between 2003 and 2011, there were 33 major public releases of Blender: a development schedule on a par with commercial applications. The frequency and regularity of the updates reassured potential users that the software wasn’t about to disappear overnight – not always a certainty with open-source projects – but while professional artists would have regarded the new features as “good”, many would have qualified that assessment with the caveat, “for free software”.

That changed at the end of 2011 with the release of Blender 2.61. Cycles, the new render engine that it introduced, was a production-capable ray tracer before ray tracing was common in movie production: at the time, Arnold was best known as Sony Pictures Imageworks’ in-house software, while V-Ray was still largely an architectural renderer.

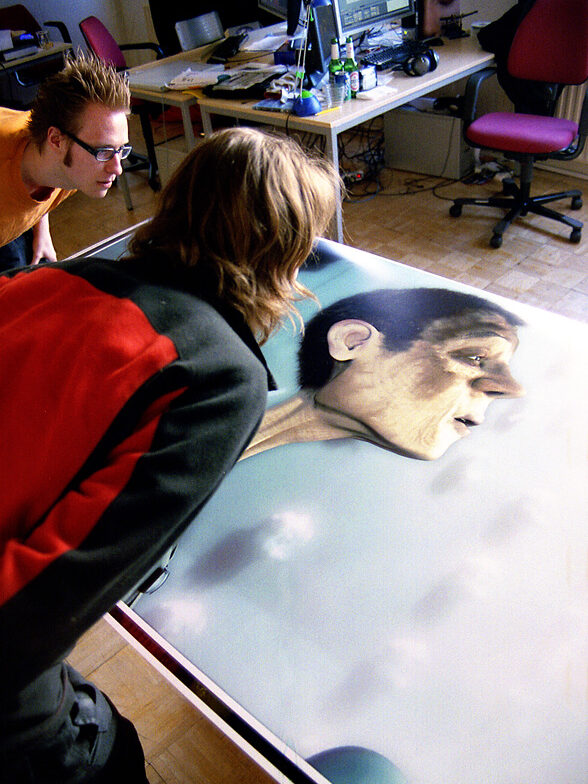

The following year, open movie Tears of Steel brought new camera tracking, compositing and grading tools – things that commercial visual effects applications tended to throw in as afterthoughts – and by the time Grease Pencil 2.0 was introduced later in the decade, it was clear that Blender was beginning to do things that no other 3D application could.

Meanwhile, major studios were taking their first steps towards open-source, albeit in the form of pipeline technologies like OpenEXR and Alembic: the idea of open-sourcing an entire in-house tool, as DreamWorks would later do with its MoonRay renderer, was still unthinkable.

As they did so, Blender began to move in from the margins. At the start of the decade, its largest users were firms in Asia and South America, some of which had switched over from cracked copies of commercial software; by 2014 it was being used on the Oscar-nominated Song of the Sea.

The following year, Pixar revealed that Blender was one of the third-party 3D applications that the studio supported for use internally, and the software finally had Hollywood’s seal of approval.

2014 – 2019: (Mis)adventures in open movie-making

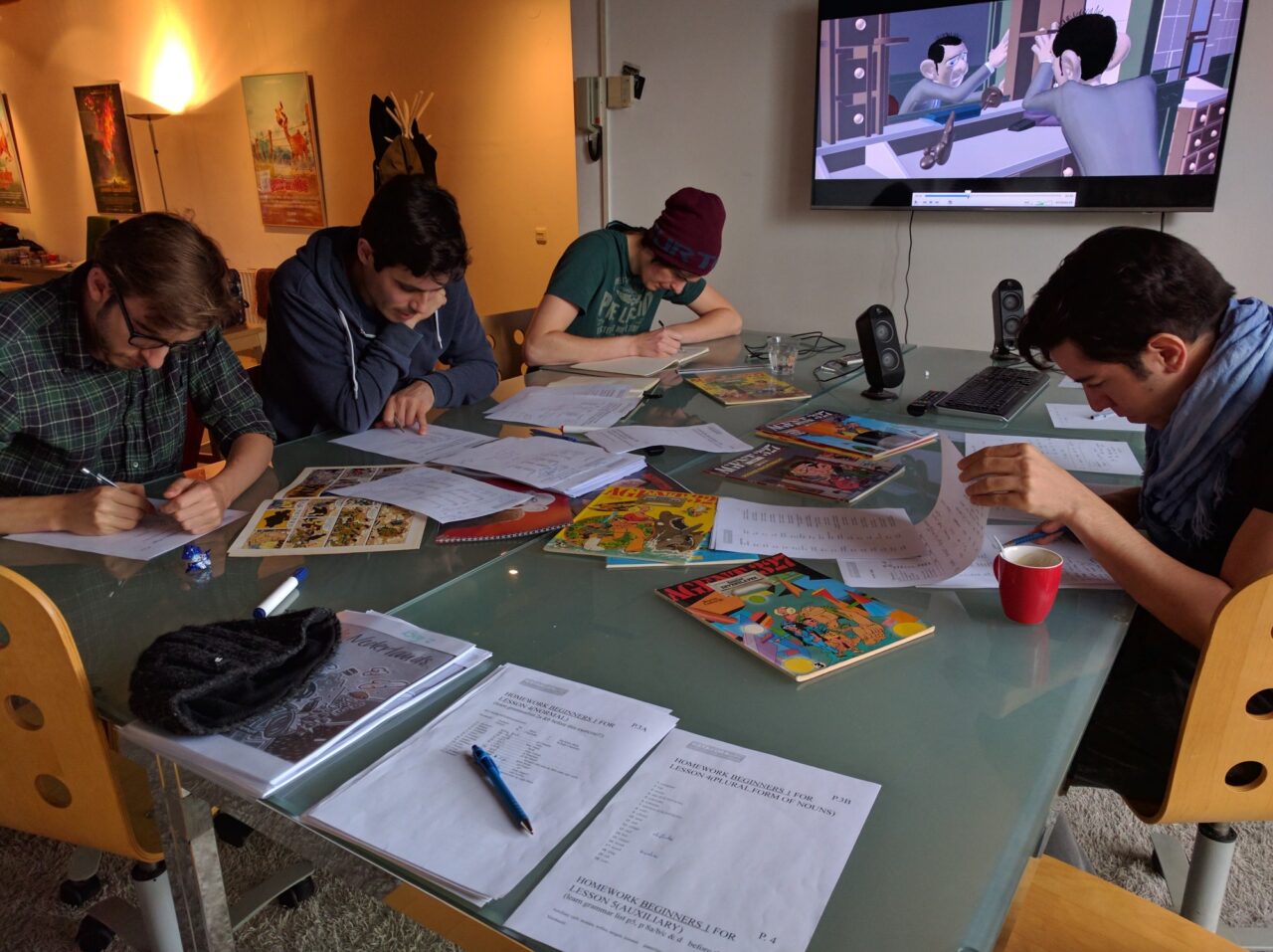

But in the second half of the decade, it often seemed that the goal of the Blender Institute was not to seduce Hollywood, but to set up in opposition to it. In 2014, the Institute announced Project Gooseberry, a crowdfunded feature-length animation, to be produced by a network of decidedly non-California-based studios, including the Oscar-winning Autour de Minuit.

While crowdfunding had worked for Blender itself, it failed to scale to movie production, with the project securing just under €300,000 of its initial €500,000 target: not far off the record for a crowdfunded animation at the time, but a long way short of the €3.5 million needed to complete the film, and orders of magnitude less than a typical Pixar or Disney feature.

Project Gooseberry was eventually scaled back to a short, the surreal Cosmos Laundromat: First Cycle, and went on to win several major animation awards, plus a nomination for a Webby Award, almost certainly making it the first short film about a suicidal sheep to be shortlisted.

The Institute had a second try with the more conventionally commercial Agent 327: Operation Barbershop, an adaptation of the Dutch comic series, produced as a teaser for a full-length animated feature. But while the trailer, directed by former Pixar artist Colin Levy, was well-received on its release in 2017 (this time, it actually won a Webby), the movie itself has yet to materialize.

However, not all of the work was in vain: the Blender Development Fund, Blender’s crowdfunding platform – introduced in 2011 and relaunched in its current form in 2018 – was to play a crucial role in the next chapter in Blender’s story.

2019: The breakthrough

Throughout the 2000s and 2010s, Blender’s interface and workflow had been stubbornly, even defiantly, different to that of other 3D applications. ‘Just because everyone else does it, that doesn’t mean it’s right,’ seemed to be the prevailing opinion in the development team.

That’s undoubtedly true, but for software to be adopted on large projects, studios need to be able to call on enough freelance artists to get them through crunch periods, and the way that Blender did things deterred many freelancers from making the switch from commercial tools. (The convention that you right-clicked rather than left-clicked to select things was a particular turn-off.)

But in 2019, following an unprecedented two years of development, that finally changed, with what was to become the most significant update in Blender history since the original open-source release.

Not only did Blender 2.80 standardize Blender’s interface and dispense with the default right-click, but it introduced Eevee: to this day, a more capable viewport renderer than those in most 3D applications, and a real unique selling point at the time. The images that early users, like Lucasfilm concept artist Jama Jurabaev and Daniel Bystedt, then Head of Modeling at Goodbye Kansas Studios, produced with it would prove invaluable in building a buzz ahead of Blender 2.80’s release.

Under the hood, the update overhauled the dependency graph, improving performance on large scenes, and introduced the Collections system, making it easier to manage assets in production. Suddenly, Blender began to look like a viable proposition not just for teams of 20, but of 200.

Outside the core software, there was a growing ecosystem of third-party add-ons, available through sites like Blender Market. Plugins have been key to the success of many professional applications, expanding popular toolsets in more focused ways, and some of those add-ons, particularly hard-surface modeling tools like Boxcutter and HardOps, proved to be a major draw to new converts.

Blender also benefited indirectly from the massive success of Fortnite, some of the profits from which Epic Games redistributed to the industry through its MegaGrants program. The $1.2 million it donated to the Blender Development Fund over a three-year period convinced other tech giants to do likewise – Amazon, AMD, Apple, Google, Intel, Meta, Microsoft and NVIDIA have all contributed to the fund – funding a rapid expansion of Blender’s development team.

Convinced by the positive PR, major studios began switching to Blender, with both Ubisoft Animation Studio and anime powerhouse Khara, Inc. announcing that they were adopting the software as their primary production tool.

By end of the year, even skeptics knew that the Blender of the 2020s would be a very different beast to the Blender of the 2000s, or even the 2010s, and as smaller commercial tools faltered, switching to open-source became not just a viable strategy for freelancers, but a career survival strategy.

2020 – 2023: Living up to the hype

The problem with extraordinary growth is that people expect it to continue, long after they have forgotten that it is extraordinary. While enthusiasts might have hoped that by now, Blender would dominate movie production, the past three years have been more about consolidation than conquest.

While the software remains widely used for asset development, its adoption in other parts of production pipelines has been slower, with the long-awaited overhaul of the character animation tools now scheduled for completion in 2025.

And in 2021, Blender lost one of its highest-profile users, the Emmy Award-winning Tangent Animation, prompting an acrimonious online debate about whether the studio’s closure was the result of its Blender-based pipeline, or its subsequent decision to abandon it. (For what it’s worth, it was probably neither.)

Nevertheless, Blender continues to be used on high-profile projects like Netflix’s Love, Death & Robots and Amazon Prime Video’s Undone, while the Blender Development Fund receives over €130,000 each month, helping to pay the salaries of over 25 full-time developers.

The software even has a grown-up new release schedule, having recently moved to a two-year cycle with regular long-term support releases. As the recent decision (thankfully quickly reversed) to break with the VFX Reference Platform reflects, it doesn’t always do what visual effects facilities expect, but then, it probably never will: Blender is an application whose development is dictated by the needs of millions of individual users, not a handful of large studios.

As it hits 20 as an open-source application, Blender is no longer a precocious child or a rebellious teen, but it’s a long way from sinking into middle-aged conformity. The software has taken on adult responsibilities without losing the youthful desire to shake up the established order that has taken it from the hobbyist community to the very heart of the movie industry. Here’s to another 20 years of rule-breaking.