The makers of Wolfwalkers, Cartoon Saloon, might well be the most famous 2D animation studio around — especially now, with Wolfwalkers’ recent Oscar and Golden Globe nominations. Of course, Cartoon Saloon are staunch supporters of traditional methods, originally developing their distinctive style as a response to the industry’s dominant form: 3D.

And yet we’re talking to Eimhin McNamara, a key figure in Wolfwalkers’ production, about Blender: the best known independent 3D software meets the best known independent 2D champions.

What gives?

Meet Eimhin McNamara

Eimhin McNamara is an educator and filmmaker based in Ireland. He still sounds a little stunned by the film’s reception: even without the Oscar and Golden Globe nominations, Wolfwalkers is one of the most critically praised animations of recent years.

Eimhin: “The response helps salve the wound of how much work it took. 22 months for the full production. I was involved for 18 of them, so it was pretty full-on.”

Of course, every feature film is complex and involves many tools. For Wolfwalkers, one of those tools was Blender, which was used for Eimhin’s part of the movie. He supervised a particularly striking series of sequences: “Wolfvision,” which shows us the film’s medieval forests and towns from a wolf’s point of view, and involved much 3D pre-visualization.

“I got the job because they knew I could figure stuff out. I come from a stop motion background, a 2D background. But whatever is needed to get stuff on-screen works for me. I’m fairly method agnostic.”

Much of Wolfwalkers remains hand-drawn; Princess Mononoke was a big reference for the directors. “Princess Mononoke included a fair few 3D shots, but guided by the idea that it wasn’t meant to look 3D. Similarly, we didn’t want the 3D elements to decide the end result.”

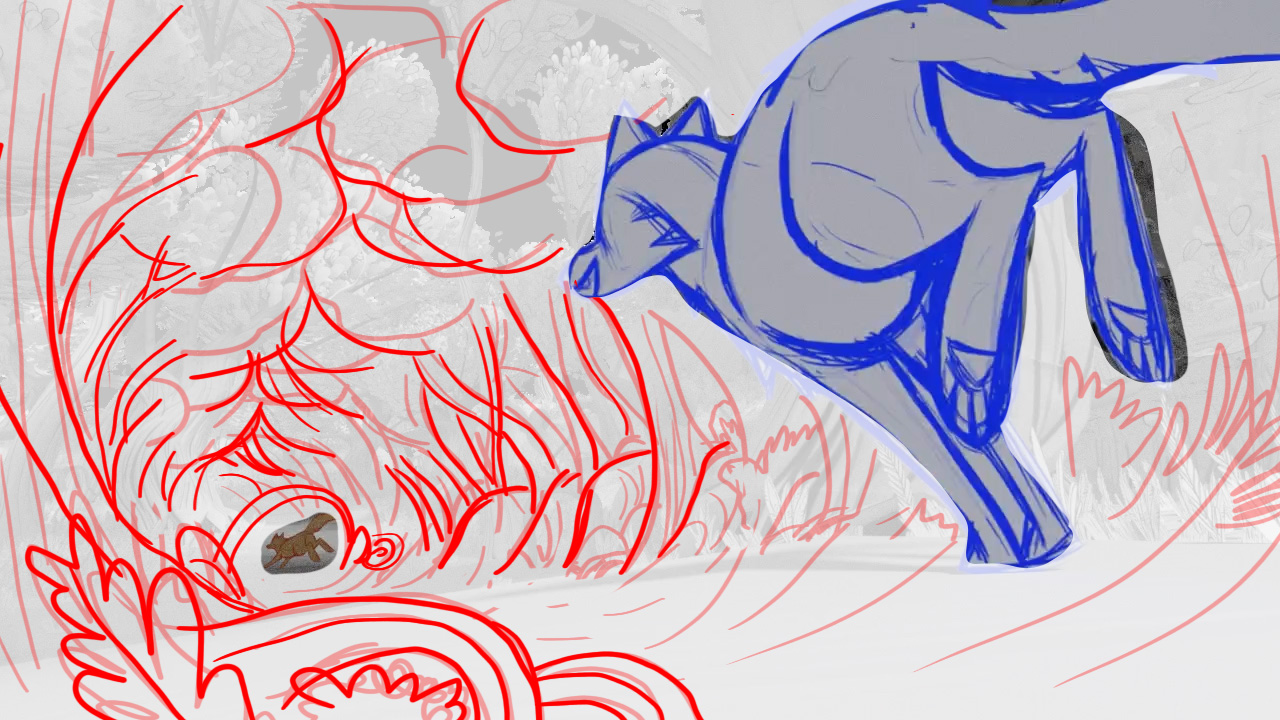

In terms of using Blender, this desire translated to mixing standard modelling techniques and arrays with Grease Pencil, plus animated assets from the film’s 2D departments.

The Vision Behind Wolfvision

“At the start of the production,” says Eimhin, “We were trying to figure out, ‘How 3D does it have to be? Or how little?’ 3D is very time-intensive. You can’t take as many shortcuts as you can with 2D. In 2D, you can draw only what you need. In 3D, you have to figure out constructions and surfaces and so on.”

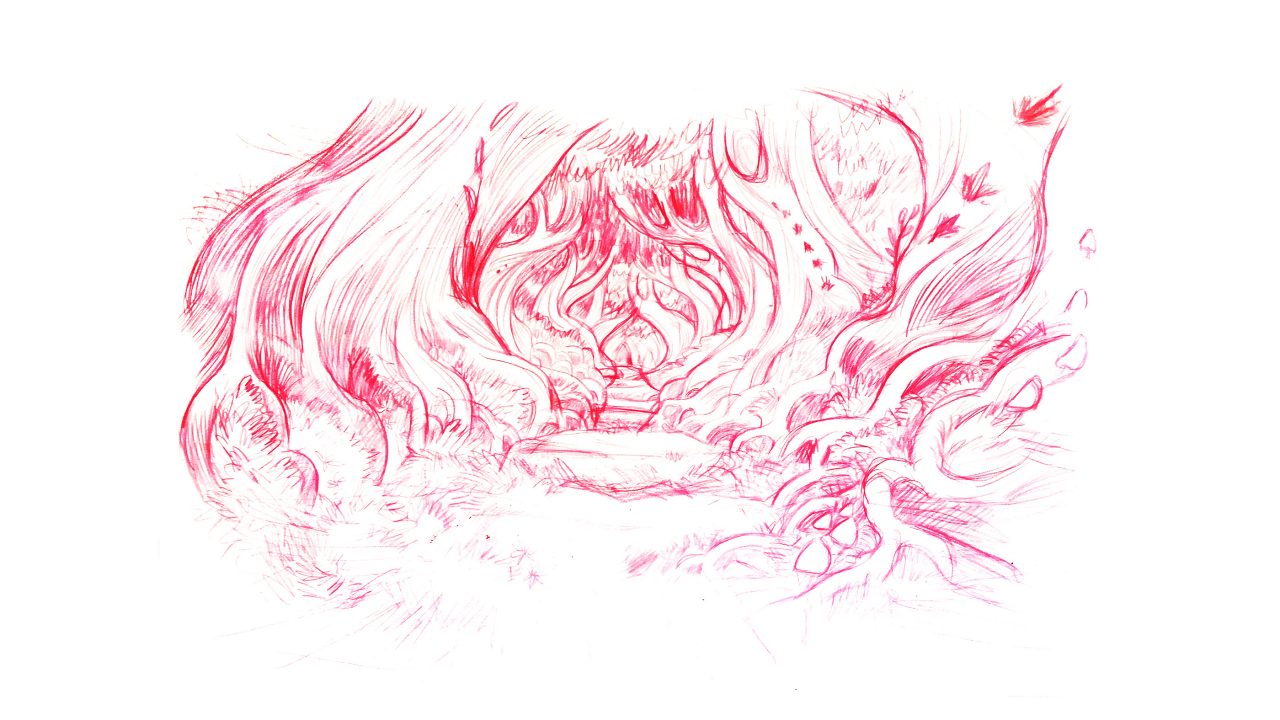

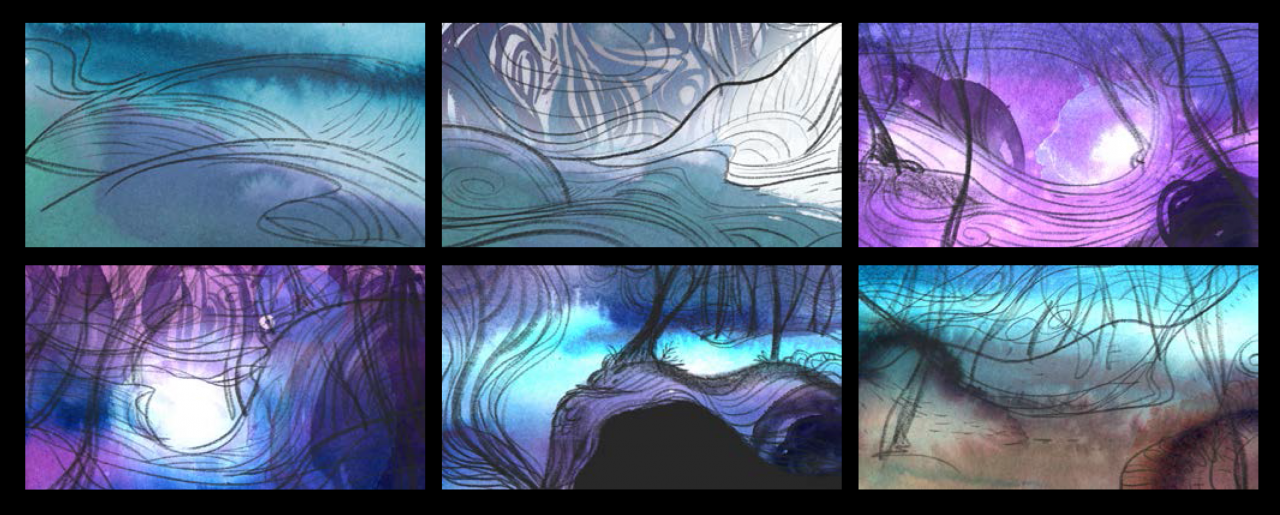

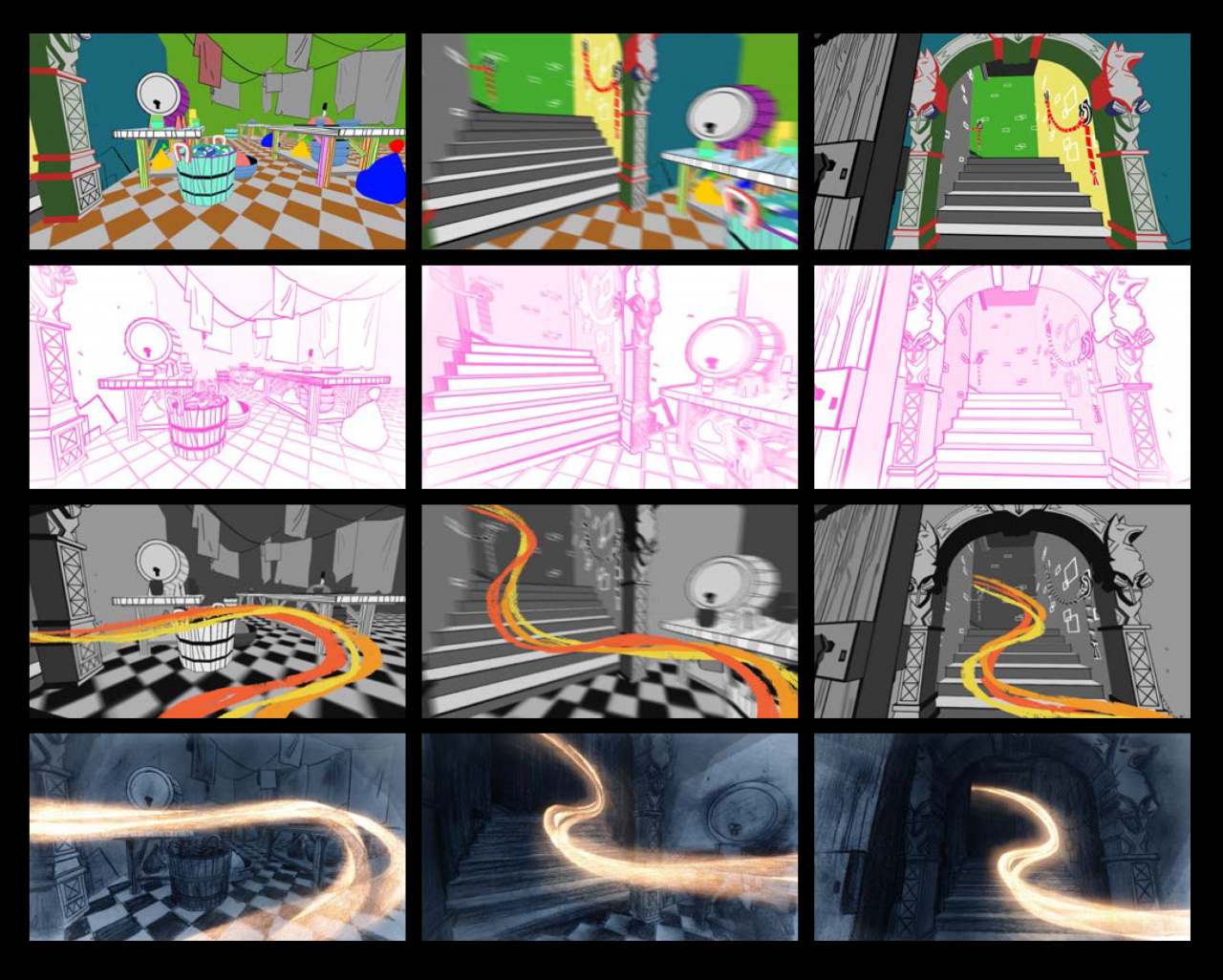

In the early stages, Eimhin and his team needed to define the depth required for each sequence. “We produced several test scenes,” says Eimhin. “I’d make a fake depth map painting. And texture it with just lines. Then I’d do a 2D character animation on top of that. We had a process where we’d print out the digital linework in a light magenta using CMYK colour process, so the colour was as pure as we could get it. Then from there, I’d just trace each image, rendering it on paper and embellishing it when needed with graphite. After that, I’d scan it back in and digitally remove the printed magenta reference, leaving only the graphite render. We would embellish it further in the composite, adding some colours. That was the first couple of weeks, just figuring out the look of everything.”

Later, Eimhin moved to Oculus and Quill for blocking, before switching to Medium for more advanced modelling. He’d import these VR creations into Blender. “We used Blender to control the camerawork, as well as for cleanup.”

Eimhin’s Wolfvision crew included two Blender artists: David McDermott, who’d worked in Japan on a number of Nintendo game titles, and artist/filmmaker Daniel Pinheiro Lima. “David and Daniel focused on the shots in the forest because they were very familiar with arrays, and how to lay things out in a more patterned way.” Eimhin laughs. “Whereas I’m a bit of a troglodyte. I’d probably just try to manually sculpt everything and slow things down. I did a lot of diorama style shots using one of the mainstream animation programs because it’s what I know best. But those shots could just as easily have been done in Blender.”

Directing Daniel and David was only part of Eimhin’s role. “My main task was to make Wolfvision integrate into the main film after David and Daniel had finished. So they’d do these rough fly-throughs and I’d draw on top of those images, sometimes with Grease Pencil, with notes like, ‘This surface should have clusters of moss, more rocks here,’ and so on. The idea behind the forest in Wolfwalkers is that there should be a flow. Everything should reinforce that, creating this tunnel effect.”

Eimhin has used Blender since the Wolfwalkers production began in 2018. At that time, Blender’s 2D animation workspace was still in its first iterations. Even then, he found it invaluable. “You could draw on top of other artists’ models with Grease Pencil, or establish camera angles. Which saves so much time in terms of giving feedback.”

As wolves “see” with their noses, Wolfvision features characteristic “scent trails.” For these, Eimhin again chose Blender. “The scent trails are tubes with path extrusions, then hand-drawn stuff on top.”

This approach of hand-drawn animation on top of 3D animation requires a high degree of care. “If you’re working on paper, tracing over and embellishing a 3D build, you have to make sure everything’s right. It’s hard to go back and change the camera angles. There are so many steps you have to redo if you want changes.”

However, this workflow has its plus points– beyond the beauty of the results. “On the other hand, you’d look at the 3D and say, ‘Okay, you don’t need to fix this now. We can fix it in the drawing stage and let the graphite marks on paper take the lead.’”

Wolfwalkers was made on a budget of roughly twelve million dollars, a tiny fraction of the 300 million spent on the average Disney film. “So we tried to be sensible,” says Eimhin. “For example, we’d use matte paintings in the background of our Blender shots. We’d ask, ‘Okay, how much depth does there have to be versus mitigating the labour involved?’ ”

A similar attitude informed motion blur. By printing out a 3D version of a motion-blurred shot and drawing over it, Eimhin and his team were able to cut extraneous details. “We’d say ‘Okay, I need that,’ or ‘That’s just busybody work. I can use scribbles here.’ Seven people would help render these shots, sweeping graphite across the paper. That way we imitated a more organic blur.”

Not Your Usual References

Artists are often admonished to resist the lure of ArtStation, and instead look for more original references. If you’re feeling adventurous, you might look at the Golden Age of Illustration and the likes of Dean Cornwell.

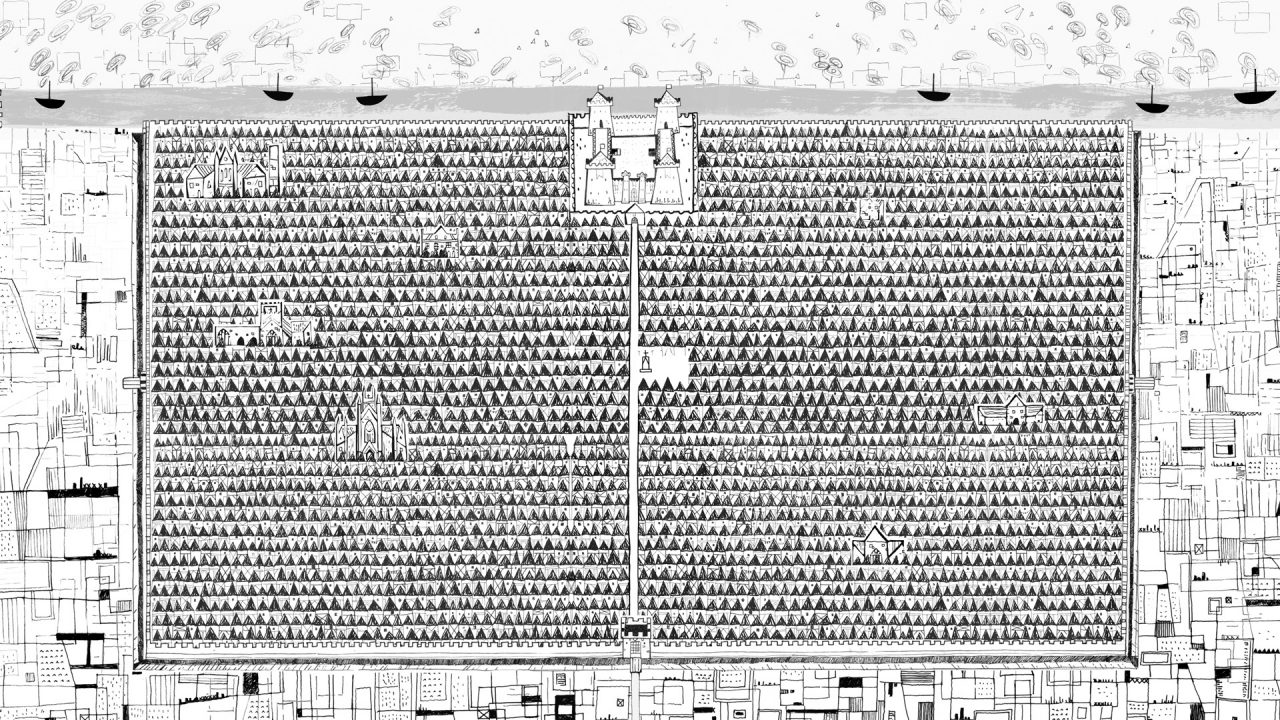

But for its trademark style, Cartoon Saloon didn’t stop at the Nineteenth Century. “That flat style is influenced by the Fifteenth Century or thereabouts,” Eimhin explains. “From medieval illuminated manuscripts, pre-Renaissance art, freezes and woodblocks and things like that. When Cartoon Saloon developed this style, it was as a reaction to 3D, because then 3D was the big thing. It was almost a contrarian outlook. The idea was ‘Let’s do what 3D can’t do and just run with it.’”

There was also a practical component to Cartoon Saloon’s artistic choices. “We didn’t have the resources to compete with 3D stuff, so how do you do what 2D does best?”

What Makes Blender Better

“For most of the production,” Eimhin says, “I was actually working on my old computer. Daniel was working on a version of Blender 2.8. David was working on another version of Blender, 2.78. So I could easily install those old versions of Blender. There was mutual intelligibility immediately, for me to do any edits. I could send files for their versions back to them. That’s a big thing for me. And it was great to see the animation workspace getting more and more refined.”

Eimhin sees the advantages of Blender’s flexibility in his role as an educator. “I teach animation at the National Film School, IADT, here in Dublin. And I’m trying to get all the students to use Blender rather than the competition because they’re such a nightmare.”

“One of my graduates made a model for one of their 2D films. It was a car. But due to Covid, we had limited access to the campus. Which meant we couldn’t get on a machine with a licence for this particular 3D application, nor could we get one through the college. Basically, this student lost access to their file. And we had to build it from scratch. If they’d made it in Blender, we’d have had access to the model from the beginning.”

“Even the community support for Blender is much more intact. And then of course you’ve got the prosumer part of it. The courses and so on, which are guided. Blender is just very democratic in terms of accessibility.”

And that accessibility helps all kinds of users, from hobbyists to the highest tiers. “There are just so many people I know that now use Blender in their studio work as well. And the more you use Blender, the easier it is to integrate it into productions. For example, in Cartoon Saloon, the technical team, such as Fergal Brennan who worked with my team, use it in scene prep. Shots of rolling plains, you can do that stuff really quickly in Blender. You don’t need to worry about how it will affect the budget. You don’t need to worry about creating a two-second shot and then feeling compelled to use it twice. Even small things like that mean Blender is a much more attractive option.”

“And I know that David McDermott uses Blender solely for his work. And Daniel uses Blender a lot for a mixture of film and game development. And also illustration. He’ll make 8-bit characters in Blender.”

“There’s just a huge amount of stuff you can do with it. Even just in terms of the sharing you can do online. On Twitter there are quite a few people who do a one-minute run through of their process, which is very helpful.”

“And the cloth simulation stuff. A lot of that can be very interesting to integrate into production as well. I encourage people to use Blender for compositing too, just to escape getting tied to subscription systems, which are quite burdensome. In Blender, you can tweak so much more. You can customize so much of Blender.”

So… What Gives?

To answer the question we began on, Eimhin notes that limited budgets mean filmmakers need to find the “shortest route to getting the shot that we want.”

Naturally, that doesn’t mean abandoning Cartoon Saloon’s commitment to traditional ways of animating. To be clear, Wolfwalkers remains an artwork rendered overwhelmingly in 2D. Eimhin: “At the end, I had a stack of drawings next to me almost as tall as I am.”

At the same time, the Wolfwalkers’ crew weren’t dogmatic about achieving their goals, and that meant the judicious use of 3D. “People don’t believe that 2D is dead anymore,” Eimhin says. “It’s just become something different. When I Lost My Body, came out in 2019, everyone was like, ‘They’re using Grease Pencil! They’re using Blender!’ And I said, ‘See, I told you guys! I told you!’” He grins. “Then we had guys in the studio saying, ‘Okay, okay. Maybe we could do a bit more 3D.”

The result is worthy of any go-to movie review adjective: spectacular, awesome, moving, gorgeous. Catch Wolfwalkers on Apple TV.

For more Eimhin McNamara, see Instagram and Patreon.

For more on Eimhin’s Wolfvision colleagues, see Daniel Pinheiro Lima’s site, and David McDermott on ArtStation. Friedrich Schaper can be found on Instagram. And Maria Pareja can also be seen on Instagram.